With our longest driving day of the trip (8.5 hours in the car), we set out to see as much as we could while driving across the “Sunflower State.” While some may think of the Plains as plain, we were determined to see interesting spots, and we did!

The Largest Easel

Goodland, KS is the unlikely destination of artist Cameron Cross’s “The Big Easel” installation. The art project includes not only the titular easel, but also a replication of Vincent Van Gogh’s “Three Sunflowers in a Vase.”

Interestingly, it is one of seven such pieces that Cross has either created or hopes to create, with the other completed projects being in Emerald, Central Queensland; Altona, Manitoba; and Arles, France.

In all, the Goodland structure is eighty-feet tall, and it is a creditable replica of Van Gogh’s masterpiece.

Further, it is located in the midst of a city park, complete with a pagoda, a lending library, and some walking trails. It was a pleasant stop while traversing the western corridor of Kansas.

Lindsborg, KS

Nestled amidst the plains of Kansas is Lindsborg, KS, otherwise known as “Little Sweden USA.” The moniker derives from the fact that city was founded by a hardy group of Swedish immigrants in 1869, led by pastor Olaff Olssen. Even today, thirty percent of the population is of Swedish origin, and it is home to the biennial Svensk Hyllningsfest.

It is a lovely town and a delight to explore. The street is lined with “Dala” horses, a representation of Swedish culture and heritage. They are cleverly done, with a “one-Dala” horse being painted green and adorned with features from US Currency; a “Blue-Colla Dala,” recognizing the workhorses in the community; and, probably our favorite, a “Salvador Dala” horse, featuring the Spanish artist’s characteristic surrealist landscape.

We also loved City Hall…

…a historic bank building originally built in 1887 (and reminiscent of the Roche Building in Huntsville, TX)…

…the quaint downtown streets, which were wonderfully walkable…

…and Swedish-themed telephone booth, as charmingly anachronistic as the town.

Small World Gallery

by Chrissy Biello

Jim Richardson is a legend in the field of photography, with countless features in National Geographic and a long list of prestigious awards to his name. His work has shaped how people see the world, especially Scotland and Midwestern America. But despite his global recognition, he calls the small town of Lindsborg, Kansas, home, where he owns a Main Street gallery and studio called Small World.

I recently had the chance to take Richardson’s The Working iPhone Photography Class over Zoom. The two-session course, each lasting two hours, completely changed the way I look at phone photography. Before, my approach was basically point, click, and hope for the best. But Richardson’s class made me realize just how much potential my iPhone camera had if I actually took the time to use it properly.

During our trip to the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences Conference, I tried to put some of Richardson’s lessons into practice. I was not sure if I was using his advice correctly, but I made an effort to be more intentional with my photos.

On the day we left Colorado and entered Kansas, we decided to stop in Lindsborg and visit Small World. To our surprise, Richardson was there in person. It also happened to be the first day of a new exhibit featuring some of his latest photographs from Scotland, Kansas, and other areas of interest.

Inside the studio, there was a lot to take in. Along with Richardson’s prints, there were books, drawings from other artists, and handmade jewelry crafted by his wife Kathy and Briana Zimmerling. Every part of the space had something interesting to look at.

Seeing Richardson’s work in person gave me a new appreciation for his photography. His photos capture people in a way that feels natural and genuine. His landscapes and wildlife shots show the same kind of attention to detail and care.

While looking around, we had the chance to talk with Richardson. Since I had taken his class online, I was excited to meet him in person. He was just as engaging and knowledgeable as he had been on Zoom. He even gave Olivia a photography tip, suggesting she use her hand as a shade when harsh light was hitting the frame. She later tried it while photographing a Henry Moore sculpture at Wichita State University, and sure enough, it worked like a charm.

Of course, we could not leave without taking a few prints home. Choosing just one was nearly impossible, but after much debate, we each settled on the piece that spoke to us the most. As a bonus, each print purchase came with a free postcard; Olivia and I chose one that featured the Great Sand Dunes National Park as we had just visited.

Before we left, Richardson took the time to personally sign all our purchases, making them even more special. The visit had already been unforgettable, but this was a very thoughtful gesture that meant much to us all.

It is clear that Richardson is not only an exceptional photographer but also a truly kind and genuine person, qualities reflected in both his work and how he connects with others. It was an honor to meet him and have the opportunity to learn from him, even if only for a few hours. I gained valuable insights and look forward to applying them to my future photography.

Birger Sandzen Museum

One of the city’s most famous native sons is Birger Sandzen, a world-renowned artist who also taught art at the local Bethany College. Indeed, Sandzen was part of the Bethany faculty for an astounding fifty-two years.

Sandzen was known for his impressionist paintings, which he created using impasto strokes and vivid, sometimes unnatural colors. The result is a striking, three-dimensional effect, making Sandzen a highly collectable artist. Indeed, his work is in the Denver Art Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, the Nelson-Atkins Museum, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and many others. But it is the Birger Sandzen Museum in Lindsborg, KS, that has the most works on display at any given time.

The Museum, founded in 1957–three years after Sandzen’s death–now houses an impressive collection of the artist’s body of work, which was voluminous. It is tastefully displayed in two galleries, with three additional galleries devoted to rotating exhibits

Sandzen’s work, which ranges from small, monochrome lithographs to expansive, colorful landscape, is effectively showcased in the gallery.

We enjoyed looking through the rooms, seeing his body of work, distinguishing among his different styles, and picking our favorites.

Chrissy’s favorite featured Rockport Massachusetts, one of several paintings Sandzen did while visiting the Bay State.

Olivia’s favorite featured the Garden of the Gods, a wonderful area in Colorado Springs, CO, where Sandzen taught in 1923 and 1924. The artist painted several such pieces in the area, and his work in Colorado was featured in 2016 at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center.

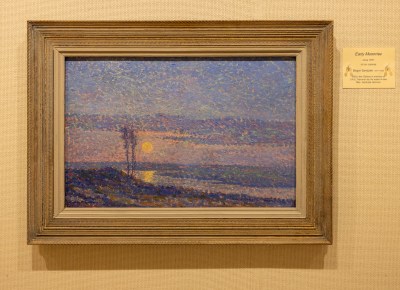

Professor Yawn’s favorite was “Early Moonrise,” where Sandzen ventured into pointillism, producing a work with strong overtones of Paul Signac.

Beyond the main gallery, the Museum also featured an exhibit by Wayne Conyers, who had some clever riffs on other artists and some very nice ceramics.

In our group, other pieces from the Museum’s collection stood out prominently. Professor Yawn found Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton pieces; Chrissy was surprised to see works by Rembrandt; and Olivia spotted two Albrecht Durer works!

Wichita State University

Following a day of driving and art-themed exploration, we doubled down and did some more! We ventured onto the grounds of Wichita State University…

…which has a public art collection of almost 100 pieces, and we soon learned that many luminaries were among them.

We began with some big-hitters–Jesus Moroles, Joan Miro, and one of Robert Indiana’s “LOVE” sculptures.

We then did a walking tour of the campus, where we met many oddly friendly squirrels, and we saw even more great art. There was Oldenburg’s “Inverted Q”…

…one of George Rickey’s kinetic sculptures…

…Auguste Rodin’s “The Cathedral”…

…another Rodin, “Grand Torse de L’homme qui Tombe”…

…a “Reclining Figure” by the incomparable Henry Moore…

…Louise Nevelson’s “Night Tree;” and a large and attention-drawing Luis Jiminez sculpture, “Sodbuster San Isidro.”

We noticed that many of these pieces had been donated by (1) collectivities of students (such as cohorts or organizations); (2) alumni; or (3) funds from the Student Government Association. As LEAP Ambassadors and students who are passionate about arts, we have been excited about TSUS’s recent emphasis on the arts. We have also offered our own arts programs, and we hope to do so again.

But seeing the investments made by current students and the SGA on WSU’s campus provided examples of how collective action by students and governing organizations could be used to beautify the campus, engage the student body, and raise the profile of the University.

as another day closed on our art tours, and we headed to Oklahoma City–following a brief stop at the Allen House, by Frank Lloyd Wright– en route to a return to SHSU.